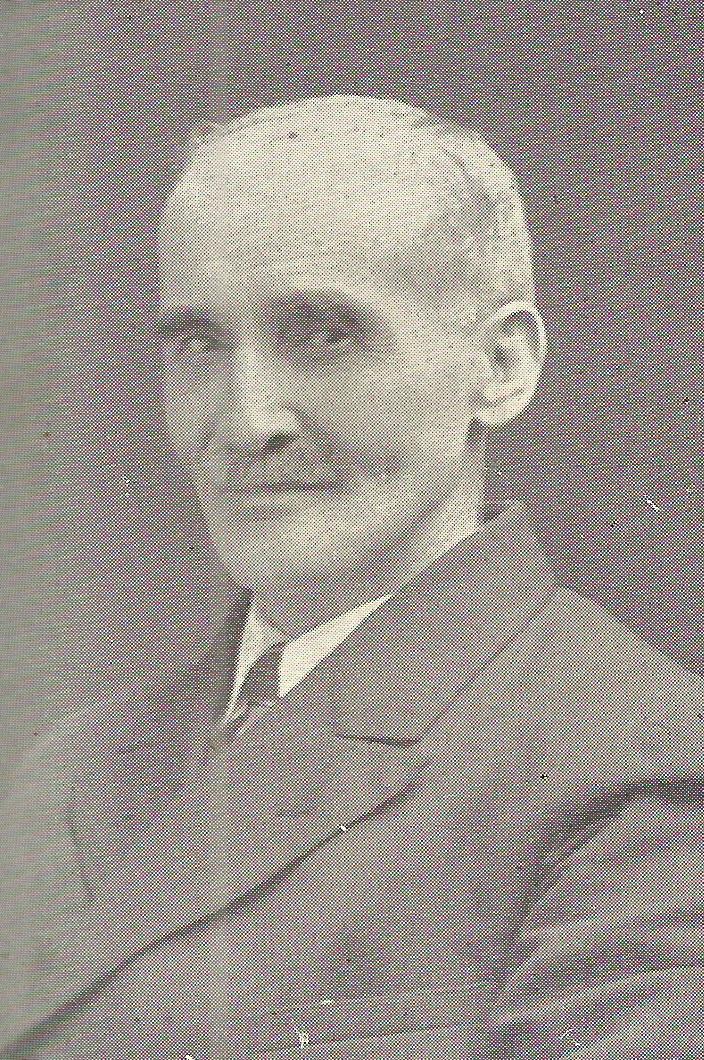

The Enigmatic Samuel Mercer

Everyone in Bay Roberts, NL, knows that Samuel Mercer (1879-1969), Episcopalian clergyman and world-renowned Orientalist and Egyptologist, was born in their town. The record of his birth is incontestable; he was indeed born in the town on 10 May 1879. And, when he entered Harvard University in 1905, he agreed with the baptismal registry, except that he had expanded his name to Samuel Alfred Browne Mercer. Five years later, when he entered the University of Munich, he seemed to have forgotten both the year and place of his birth! “Ich bin am 10 Mai 1880,” he began his resume, “in Bristol, England geboren.”

The two errors – 1880 and Bristol – subsequently entered the reference books, and became the gospel – except in Bay Roberts, where he is venerated as a local boy who made big. The prestigious Current Biography went so far as to speculate on how Mercer ended up in Bay Roberts in the first place!

“At an early age,” the book hypothesized, “Samuel Mercer was taken to North America where he spent most of his boyhood and youth in Newfoundland.”

The question is why Mercer instigated the hoax surrounding his birth. It is a question that readily invites investigation. The holder of twelve degrees, the author of twenty-nine books and a linguist who spoke fifteen languages, he may have wanted simply to forget his poverty-stricken childhood in Bay Roberts and, at the same time, lend credibility to his many and varied accomplishments. Bristol, England, may have sounded more stately to him than Bay Roberts, Newfoundland.

A distinctive Newfoundland regional dialect – the north shore of Conception Bay which exhibits a loss of “r” after vowels – completely fooled a reporter for The New York Times in 1952. The journalist was impressed by what he perceived as Mercer’s “native British accent.” And, an expanded name, Samuel Alfred Browne Mercer, may have carried a more scholarly ring than the mundane Samuel.

A subsidiary factor is drawn from Mercer’s A Brief Autobiography, which he wrote in 1958. At seventy-nine years of age, he dated his birth in 1880 and wrote giddily that it was “the year in which Gaston Maspero [1846-1916], the famous French Egyptologist, discovered the inscriptions in the five Sakkara pyramids in Egypt.” In 1952, Mercer had completed a six-year task of translating these hieroglyphics into English. The historical link between his work and Maspero’s find was, in Mercer’s mind, too close to pass up. His claim to have been born the same year as Maspero’s find backfired, though, because the latter did not make his discovery until 1881. Mercer still missed by a year!

This is but one of many hoaxes that have been foisted upon the public. In the case of Samuel Alfred Browne Mercer, an individual of international repute, for personal reasons, threw a veil over the details of his birth. And, he allowed the hoax to persist until a future biographer rechecked the records. This is a clear example of how a hoax can become entrenched in the accepted version of events.

David Mainse on Eugene Vaters

After reading about the passing of television host and founder of 100 Huntley Street David Mainse at 81 on 25 September 2017, I went to my correspondence file to see whether I had any letters from him.

On 1 August 1988, while researching the life and ministry of Pastor Eugene Vaters (1898-1984), general superintendent of the Pentecostal Assemblies of Newfoundland (1928-62), I asked Mainse for his impressions about the Newfoundland Pentecostal pioneer.

“He was a great blessing to us,” Mainse begins his response, dated 28 August 1988. Featuring Vaters on 100 Huntley Street was, Mainse adds, “like having one of God’s patriarchs as our special guest.

“Eugene Vaters is a man of towering statue, in my experience of ministry. I’ve heard him preach. I’ve visited in his home and I have seen the results firsthand of his apostolic calling in the great success of the Pentecostal Assemblies ministry throughout Newfoundland. He was and continued to be, in my thinking, to the Church a figure of great importance. In the history of our Nation one would have to draw an earthly comparison to [John A.] MacDonald [1815-91) or [George-Étienne] Cartier [1814-73], some of the early Fathers of Confederation. I don’t wish to minimize the importance of political contribution that these men made to nationhood, but the establishment of the Kingdom of God on earth is of infinitely greater importance than the work of anyone following a political calling.”

When Vaters’ daughter, Pauline Shaw and her husband Geoffrey were with 100 Huntley Street for several years, “the character of Eugene Vaters was very much a part of their lives,” Mainse writes. “I saw and appreciated his legacy daily during the time.”

When Mainse was in Vaters’ presence, he “sensed an unbending integrity and yet a heart full of compassion and understanding. In short, a man who had, throughout life’s journey, became conformed to the image of Christ.”

Actually, Mainse knew both Eugene Vaters and his wife, Jennie (1895-1986). “Together,” he reminisces, “this couple was a formidable team striking fear into the hearts of the enemy and planting the banner of the cross firmly throughout Newfoundland and Labrador and having a great influence far beyond those shores.”

High praise indeed!

The footsteps of the Sorbonne trio

In his book Newfoundland’s Believe It or Not! Jack Fitzgerald relates a great hoax that in the 1930s rocked two continents with laughter. You can either go out and buy this book, or read the story here!

In 1933 in Paris, the Chamber of Deputies, the name given to several parliamentary bodies in France in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, spent weeks discussing debts owed the United States by European countries as a result of World War I. Public attention too was focussed on the issue.

Each member of the Chamber contributed to the discussion. Three students at the Sorbonne, the historical house of the former University of Paris, were convinced that some of the Deputies knew absolutely nothing about the States or, indeed, the Western Hemisphere. The trio determined to prove the ignorance of contemporary politicians.

A few days later, 72 members of the Chamber received a professionally typewritten letter. The letterhead read: Paris Branch, Ethnical Defence League of Newfoundlanders and Guatemalans, New York, Headquarters, 43 Seventy-Second Street, N.W. 2.”

The letter began with an appeal to President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

“You know that two States of the Republic of the United States are deprived of a majority of the privileges enjoyed by the other 42,” the authors of the letter declared.

“They are the States of Newfoundland and Guatemala,” they continued. “Newfoundland, as you know, is inhabited by two million people of Spanish origin who still speak Spanish since Cortes[-Real] conquered the country from the Incas; while the Guatemalans speak Portuguese from the time Don Pedro of Syracuse conquered the country in 1456.

“As just one example of injustice, these two States are represented in the United States Senate by only one Senator, whereas others, such as New York, have 12.”

The remainder of the letter was a similar mix of fact and fiction.

The most outrageous result of the hoax was that nine of the 72 Deputies who had received the letter responded to the nonexistent Ethnical Defence League of Newfoundlanders and Guatemalans, promising their undying support for the cause!

As one would expect, once the story got out, the two continents convulsed with laughter. The incident may not be the hoax of that century, as some would claim, but it deserves honourable mention in the history of good-natured deception.

Bill Rowe’s report card on the premiers

Bill Rowe is a veritable book-writing machine! His literary output is prodigious.

Pick the genre of your choice: fiction, collected columns, political memoir, public policy, history… There’s something in his oeuvre for every reading taste.

I haven’t yet finished reading his 2015 book, The True Confessions of a Badly Misunderstood Dog, as much as I want to. I am a shameless dog lover, who has laughed and wept over my pets. I once read John Grogan’s Marley & Me, but my eyes were blinded by tears, and I vowed to never again read such a heartbreaker. After having lost two dogs, can I bear reading what I think might be another tearjerker about a four-legged animal?

But I can and do read about two-legged animals, especially those of the political stripe. Bill Rowe is my favourite guide to recent politics in Newfoundland and Labrador. He whetted my appetite with titles like Danny William: The War With Ottawa, Danny Williams: Please Come Back, The Premiers Joey and Frank, No Punches Pulled: The Premiers Peckford, Wells, & Tobin, and now…

The Worst and Best of the Premiers and Some We Never Had is, as the subtitle suggests, “a political report card.”

The Worst and Best of the Premiers and Some We Never Had is, as the subtitle suggests, “a political report card.”

How should Newfoundland and Labrador’s political leaders during the nearly seventy years of Confederation be graded? Bill set for himself a demanding assignment, grading some forty-two individuals who led the various Parties into a provincial general election, ranging from a high of 85% (a tie between Joseph Smallwood and John Crosbie) to a low of 20% (a tie between Jim Higgins and Gus Duffy).

While Bill strove for objectivity – is objectivity even possible? – the marks he assigned reflect his personal likes and dislikes. Readers will quibble with some of his grades.

As I read, I wondered about where on the scale between 0% to 100% Bill himself would be placed. Lo and betide, when I reached page 77, I read these words, “if I had qualified for a ranking here, I would have placed myself, based on the gap between what I had aspired to achieve and what I actually achieved, at the lower end of the scale.”

I would give Bill full marks for writing the way he did, with what he calls his “brutal frankness” and “‘warts and all’ approach.” Admittedly, it may not help him to, in the words of Dale Carnegie, “win friends and influence people,” especially those about whom he writes, but it makes for entertaining and thoughtful reading.

Following a trip I won to Russia in 1978, I spent a nostalgic hour viewing Peter Ustinov’s Leningrad. Later, William Casselman, writing in Macleans, stated, “This is the Leningrad of Peter Ustinov. Not mine, not yours perhaps, but his alone – quirky, flawed, riveting.” I don’t know about the quirky and flawed part, but Bill’s book is definitely riveting.

The Worst and Best of the Premiers and Some We Never Had is published by Flanker Press.

How Ya Gettin’ On?

Some writers are so well known, they don’t have to use their real name. Case in point: Snook, aka Pete Soucy. The title of his book: How Ya Gettin’ On? Snook Writes About Stuff.

Snook is no stranger to Newfoundlanders and Labradorians. He has hosted his own talk show on VOCM. He has also hosted his own CBC variety series. He has released several videos, CDs and DVDs. And this is only part of the stuff he’s been doing for over twenty-five years.

I’m partial to NTV’s evening news coverage. Sometimes, when  I’m in another part of the house, I hear the unmistakable voice of the fast-talkin’ Snook, “Howyagettinon?” I rush to the TV, to hear what words of wisdom he will pass on to viewers. I am rarely if ever disappointed. He’s one of a kind. And, as he might say, “Tank God for dat!”

I’m in another part of the house, I hear the unmistakable voice of the fast-talkin’ Snook, “Howyagettinon?” I rush to the TV, to hear what words of wisdom he will pass on to viewers. I am rarely if ever disappointed. He’s one of a kind. And, as he might say, “Tank God for dat!”

Snook may not have made it to the cover of Atlantic Books Today, as he has The Newfoundland Herald, but he has made it to back of the literary magazine. There, he describes himself as “a proper downtown, St. John’s, Newfoundland ‘Corner Boy,’ ” who mostly just hangs around, “shootin’ the breeze.”

He blames – uh, credits – Mother Nature for making him the way he is, “forever looking for a light, a laugh, and a milder mood.”

How Ya Gettin’ On? is a compilation of weekly columns which originally appeared in The Newfoundland Herald. Such compilations don’t always work, but this one does, as it reflects a year in the thinking of one of the province’s funniest guys. There’s no doubt about it: Snook has a wicked sense of humour.

In the dedication of his book, he makes reference to his high school principal, Mr. Mullett, who always declared that he would “Never do nudding, never be no one, and always be proper useless.” The clincher is when Snook asks rhetorically, “Where’s your book to, Mullett?” I wouldn’t want to be Mr. Mullett today!

“The world is magic,” Snook suggests, “and writing just might be the best of it.”

If you decide to read Snook’s book, to be forewarned is to be forearmed: Be ready to experience some aching belly laughs.

As Snook would say, “Right on.”

How Ya Gettin’ On? Snook Writes About Stuff is published by Flanker Press.

What to Read in the Bathroom

It’s been several years – decades? – since I’ve gone to an outhouse. But the bathroom attached to my office provides the same services. Because of the time spent in the facility, it is useful to have at hand a ready supply of reading material. There’s nothing quite so boring as sitting and staring at a blank wall, not unlike watching paint dry. Now, thanks to Flanker Press of St. John’s, and a gentleman who goes by the moniker of Grandpa Pike, I have a brand new book to add to my stash of bathroom reading, Grandpa Pike’s Outhouse Reader.

Laurie Blackwood Pike grew up in Stanhope, NL, but, leaving when he was four years old, he also grew up in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Outhouses were common in the 1940s and 1950s.

Laurie Blackwood Pike grew up in Stanhope, NL, but, leaving when he was four years old, he also grew up in New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. Outhouses were common in the 1940s and 1950s.

“On the wall beside the hole were strips of paper cut from an old Eaton’s catalogue, or the Family Herald, nailed in place, or sometimes laid in a pile within reach of the seat. While you were waiting for nature to take its course, … you used these strips the way you would use toilet tissue today.”

The Eaton’s catalogue and Family Herald may be things of the past, but, Grandpa Pike suggests, “people everywhere still read in the bathroom.” He hopes that his book “will take your mind off the more mundane.”

He tells his stories in eight chapters, umbrellaed under the good old days, animals, sports, life, the Duke, people, sales and travel. All 70 of them are humourous, inspiring and, sometimes, thought-provoking.

“A book like this … contains short reads, and you can simply fold down the corner of the page when done.” I personally prefer to not dog ear my books. “Upon your next visit, you might even choose a story at random, the length of which you’ll determine by estimating the time required to complete the job.”

Bathroom users and book readers will have their favourite stories. Grandpa Pike’s animal stories especially resonate with me. You know, he’s a very punny guy. In “Dawn,” he writes about the time he had to give his cat away because he was moving. His ending is classic: “It is indeed a long night that has no dawn.”

Grandpa Pike’s Outhouse Reader is not the kind of book to read in one … ah … sitting, then relegate to a shelf. Keep it on your vanity and read a story or two as the need arises.

Art Love Forgery

There were approximately 19,900 new books published in Canada in 1996, the latest year for which statistics are available. Even if I were to read two a week, it would take me 200 years to read ’em all! So, I must choose carefully which books I read.

As a history aficionado, I recently read Art Love Forgery, Carolyn Morgan’s foray into published fiction based on fact.

In 1880, Alexander Pindikowsky, a Polish artist working in Heart’s Content, is arrested for the crime of forgery.

In 1880, Alexander Pindikowsky, a Polish artist working in Heart’s Content, is arrested for the crime of forgery.

Morgan has been fascinated by this story since she first heard about the Pole.

“Since I am a visual artist,” she says, “his story was all the more compelling to me.” She wanted his “quite unusual” tale to “come alive.”

As a university student writing history papers, she “always read historical fiction first to get a sense of the time period and the historical figures. Reading a novel was far less tedious for me than reading dry historical documents.”

By crafting Pindikowsky’s story as a novel, Morgan was able to entertain her readers and educate people “about a slice of Newfoundland history in the process.”

Art Love Forgery is informed by an amalgam of “stories and characters from my own family history” and an awareness of “the cultural mind-set of the time.”

Pindikowsky was sentenced to prison; part of his sentence included designing and painting ceiling frescoes that can still be seen at Government House in St. John’s.

“Very progressive was the idea of using a prisoner’s talents during his incarceration instead of having him languish in a jail cell.”

Visual artistry has been part of Morgan’s life, she explains, “starting as a young girl designing and creating hats and clothing for my dolls.”

Studying art locally and spending two art holidays in France and one in Italy, studying painting en plein air, she now sells her paintings, textile work and metal art work.

She says that her visual work is based on inspiration.

“My artistic expression is all about communicating ideas and stories. My work often reflects the struggle between the industrialized/technological world and the natural world. When I am inspired, my imagination processes images in the form of a visual story. A person, place, leaf or seedpod, a phrase in a book or a fragment of conversation, can trigger a torrent of visual images that will condense into an artwork.”

In Art Love Forgery, she writes “about an artist who is part of Newfoundland’s history – a happy combination for me.”

In case you are wondering, yes, the Love in the title indicates the story of a forbidden love in the capital city in the nineteenth century.

Art Love Forgery, which is published by Flanker Press, is a good read. Morgan draws the reader in through her artistic imagination. The overriding question is: How will the love affair between Alexander Pindikowsky and Ellen Dormody evolve?

The book will also “foster a curiosity about other characters and events from our rich history,” which is one of the things Morgan wants people to take from her novel.

A fire at Brigus

It was Wednesday, 25 September 1935. Seventy-five-year-old Nicholas Smith of Brigus was in the middle of writing his memoirs. The book would be released the following year by the English firm, Arthur H. Stockwell, Ltd., under the title, Fifty-Two Years at the Labrador Fishery.

It was Wednesday, 25 September 1935. Seventy-five-year-old Nicholas Smith of Brigus was in the middle of writing his memoirs. The book would be released the following year by the English firm, Arthur H. Stockwell, Ltd., under the title, Fifty-Two Years at the Labrador Fishery.

Humphrey T. Walwyn (1879-1957), Governor of Newfoundland from 1936 to 1946, wrote the foreword to Smith’s book, referring to it as “a work of great inspirational value and historical interest to those who today follow in his footsteps.” The Englishman enthused that the author “gives to the reader an insight into the sterling character of the Newfoundland fisherman. Greater indeed than the industry itself are the courage and undying optimism which inspire him to carry on in the face of almost insurmountable difficulties. Greater indeed than the mere commercial value of the total catch are the character and resourcefulness which go into the production of a single quintal of codfish.”

Suddenly, as Smith was buried in his manuscript, a fire started in a house halfway down Grave Hill, which was one of Brigus’ better residential neighbourhoods. Much of the town’s businesses, including the premises belonging to J. & G. Smith, Captain Azariah Munden and Captain Nathan Norman, were located there. Both captains owned homes not unlike English castles which were, Smith recalled, “a picture to see.”

The fire spread to the adjacent building, then the cooperage where R. F. Horwood had lived as a child. From there, the flames lit another house and coal shed, then quickly ignited the Pomeroy dwelling and stores across from Smith’s home. The fire jumped the street, a mere thirty feet from where Smith was writing his autobiography.

“It greatly affected my brain and ability,” Smith admitted. He facetiously added that he had not been “over-stocked with either before the accident occurred!”

During the following week, Smith could barely write his own name, let alone continue writing what would become a 56,000-word book!

The author, who was blessed with a keen sense of humour, acknowledged, “I fancy now that I have got things down here that I should have left out, and have left out some funny incidents that I should have included.” He encouraged the reader to “take the will for the deed and forgive my shortcomings under the circumstances.”

A flood at Brigus in 1907. Photo courtesy J. J. Winter.

The fire was a disastrous and devastating one. Before the conflagration was brought under control, largely after the arrival of the pumper from St. John’s, sixteen structures were destroyed. Smith himself came to within a hair’s breath of losing his home and all his possessions. He and his family, he suggested, would then have “been on the street in my old days.”

As it stood, his daughter and son-in-law lost their home, which was, he wrote, “a fairly good one for a fisherman to possess.” The house boasted nine rooms and a grocery store on the ground floor; the basement stored 100 tons of coal. Fortunately, most of the furniture, as well as the items in the shop, were saved. Unfortunately, no insurance was carried. Some of the other people who had suffered loss were covered, but most were only partly insured.

Smith suspected that, if the residents of Brigus at the turn of the twentieth century could return, they would be grief-stricken to “see the once prosperous Grave Hill, now a place of fallen brick and mortar.” Smith hoped the buildings which had been destroyed by the fire would be rebuilt, but he was practical enough to realize that “time alone can tell.”

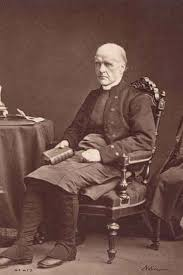

A bishop at Bay Roberts

Newfoundland’s second Anglican bishop, Edward Feild (1801-76), was consecrated in Canterbury in April 1844. Shortly after, he assumed duties commensurate with his position.

He began a private diary, in which he reflected on his challenge and detailed his voyage. He was preoccupied with church architecture and arrangement, colonial practices for church ritual, and the erection of a new cathedral. He included his personal opinions of both public figures and clergy, not shying away from passing judgment when he felt it was necessary.

Today, it is instructive to review the bishop’s experiences at Bay Roberts on 30 July 1844.

Feild found the settlement to be “very long-struggling.” To reach the church, he “proceeded along a very decent road upwards of a mile.”

Nearing the church, he spied the parson who, apparently, “had been expecting us in the morning and had designed that his people should receive the Sacrament at my hands.”

Bishop Edward Feild

The Anglican minister at Bay Roberts in 1844 was Robert Traill Spence Lowell (1816-91). He is remembered as the author of New Priest in Conception Bay, the first novel ever to be based on firsthand experience of Newfoundland life.

Born in Boston, Massachusetts, Lowell trained for ministry in the Protestant Episcopal Church. In 1842, he was admitted for ordination.

That fall, Lowell met Aubrey George Spencer (1785-1872), Newfoundland’s first Church of England Bishop, later following him to Bermuda.

Lowell was deaconed in December and priested in March 1843. He served as domestic chaplain to Bishop Spencer and school inspector.

Lowell requested to be transferred to Bay Roberts. Arriving in Newfoundland in May 1843, he became the third resident minister of St. Matthew’s Anglican Church.

Except for a three-month stint in the States in 1845, when he married Mary Ann (known as Marianna) Duane of Duanesburg, New York, Lowell lived in Newfoundland until July 1847. The couple had three daughters and four sons. Their first child was born in Bay Roberts in 1847.

Lowell took Feild to the schoolroom, where the American bragged about the Sunday school children who, in his opinion, were “well instructed in the church Catechism.” Feild begged to differ.

Lowell also boasted of the numbers he had enlisted in Sunday school. He had established a daily afternoon church service. He had also obtained and fenced ground for a cemetery. He had “great influence” with people.

Feild committed his caustic feelings about Lowell to his diary: “He is a genuine American – a young and unfortunately a single man, [who] fancies himself a decided Churchman.” His ways were “truly American.”

For example, Lowell had a dog by the name of Chrysostom. “The dog was introduced to me as a son of the Church,” Feild noted humourlessly.

Chrysostom accompanied his master and the bishop to the church, evidently “a common practice.” Field was not amused.

Feild was also unimpressed with the way Lowell “said the prayers,” making “such pauses between the sentences of the Confession that it was quite painful to hear him.” Feild thought Lowell had simply put on a performance.

Not only that, but “people kept coming in during the whole service, and the children were moving about, coming and going out in a degree that was almost intolerable.”

Feild mounted the pulpit to preach. Suddenly, “John Chrysostom marched deliberately up the church, as it might be supposed to inquire who was got into his, or his master’s, place, but as it turned out to join his master at the altar!”

Decidedly upset, Feild stopped preaching and insisted that the dog be “thrown out, which his master, in great confusion, was obliged to perform.”

The bishop noted in his diary: “I greatly fear that Mr. Lowell has another American gift, viz. that of lying,” as Lowell had assured the bishop that the canine would not venture “beyond the vestry.”

Following the service, Feild accompanied Lowell to his lodgings, which consisted of two small rooms. The American endeavoured to make the Englishman “feel more comfortable and at ease by expatiating on the house he shortly intends to build,” a stone structure on a site he had already obtained.

Lowell served his guest plenty of tea, bread and butter, along with “some very nice scrods – which is the young cod – and was the first variety of the fish I have liked.” Feild sarcastically noted, “The fishermen cook it better than professed artists.”

Lowell then “informed us of his powers and perfections, among other things equally wonderful that he was regularly descended from Mahnus Troil,” a character in a novel written by Sir Walter Scott (1771-1832).

Bishop Feild then took his leave of Bay Roberts and moved on to neighbouring Port de Grave.